P Verified Log 5: Single Producer And Outlook

In our previous post, we debugged complex race conditions in our failure-handling mechanisms. Our log system can now survive node failures and continue making progress through segment transitions. Is this enough to build a cloud database using our log system? There is still one missing feature that would make building a real system much easier: single producer guarantees.

The Split-Brain Problem

Imagine the following scenario: we use our log as the storage backend for a transactional database, i.e., the database is the producer of our log (and also the consumer. Then, the database node goes down. This is no problem for us, we can just spawn another one (e.g., using kubernetes) and continue (the content of the log is not lost).

But what if the previous node comes up again? Or it was not even down, there was just a temporary network partition causing our health checks to fail. Now we have two databases thinking they can use the log which will lead to inconsistent data - a classic split-brain scenario. It would be nice if our log had a built-in mechanism to guarantee that there is only a single producer. In this case, once the new database node has taken over, the old one is not allowed to write to the log anymore.

Graceful Takeover

A simple solution could be as follows: the new producer simply asks the coordinator for a new segment. This will cause the old segment to be closed and the old producer cannot write to the log anymore. However, there is a problem. As described in the previous blog posts, we require that the producer tells us the number of committed entries of the current segment which the new producer will not know.

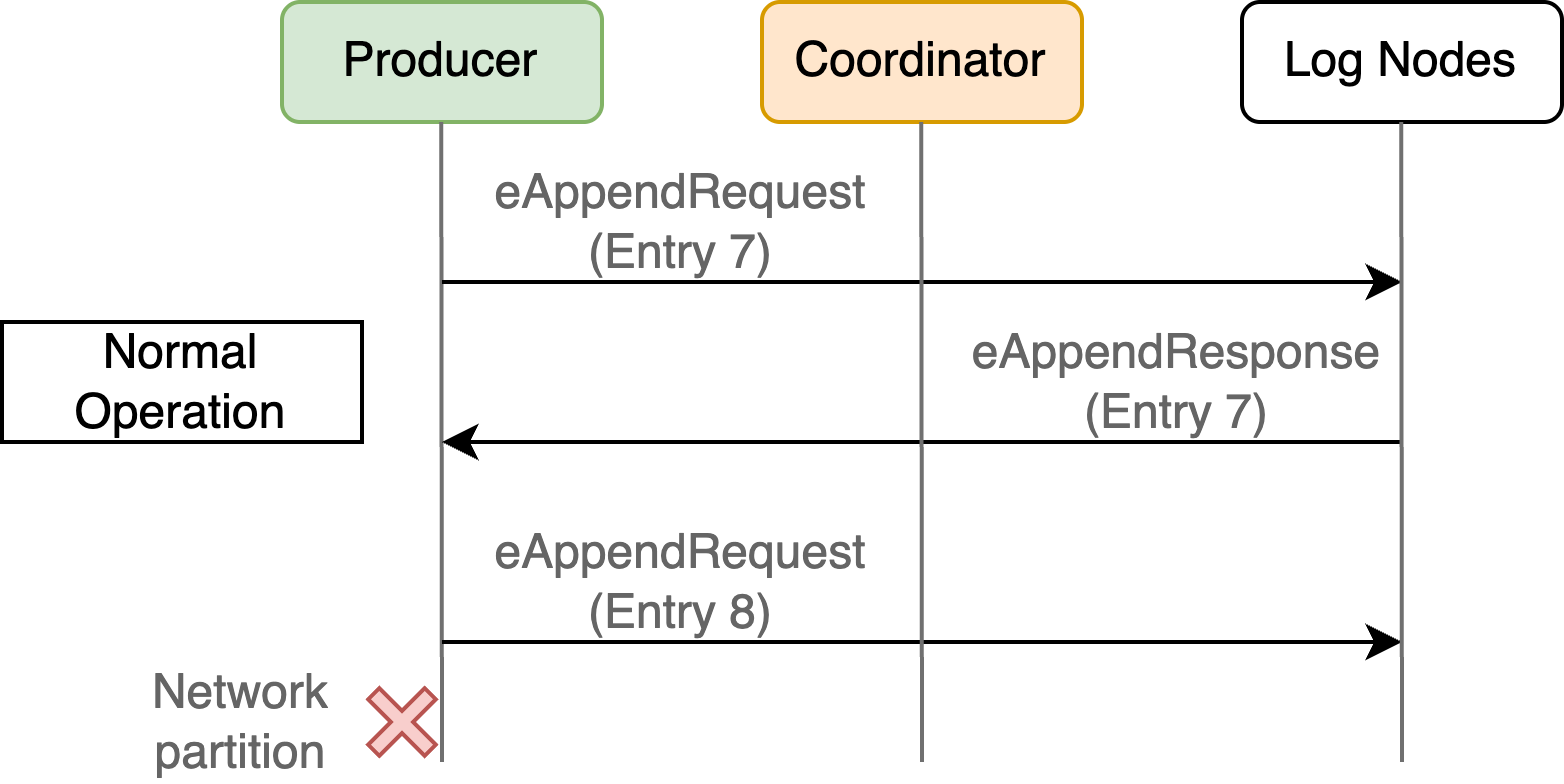

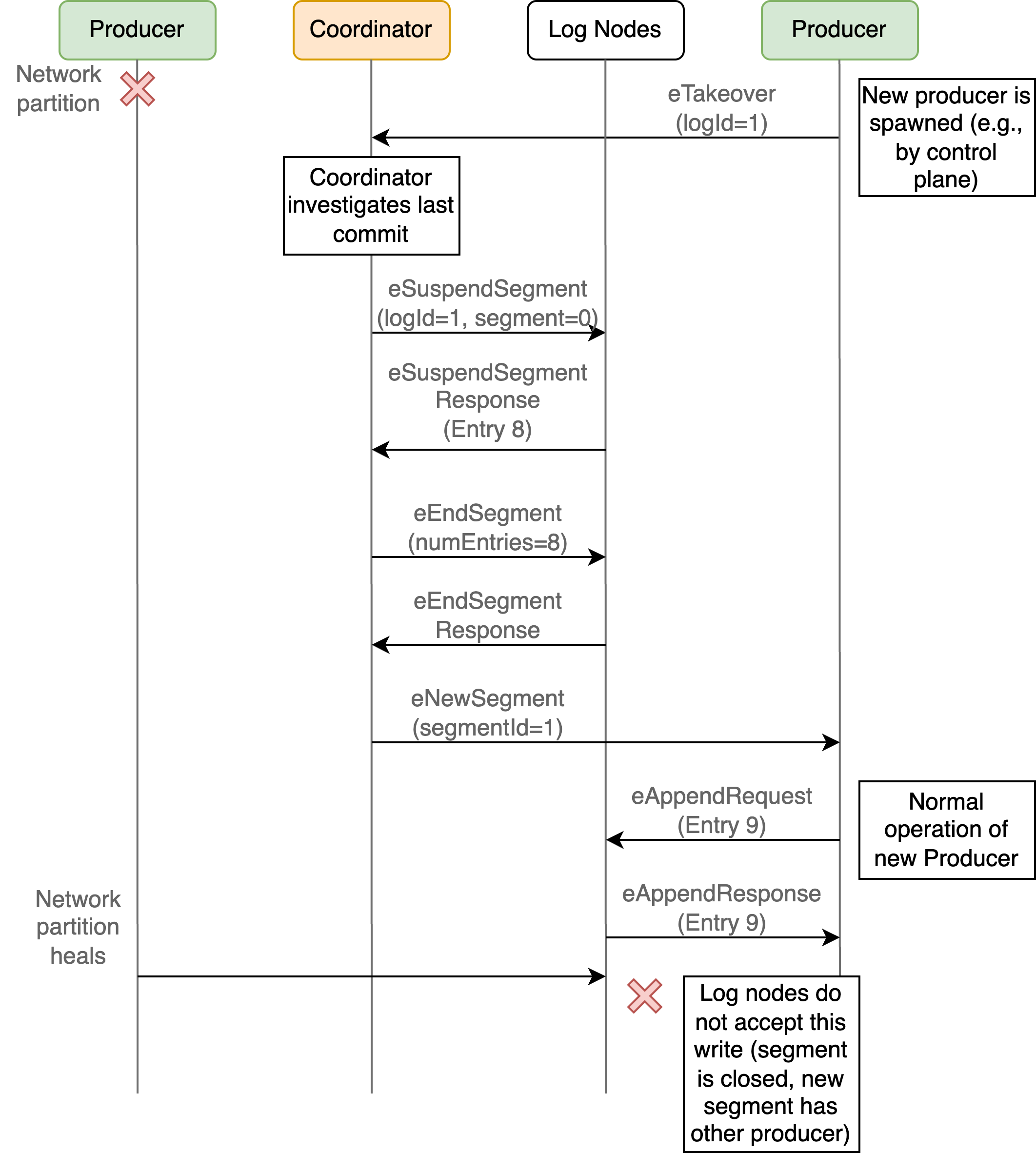

The real solution requires an extra step: the coordinator contacts the log nodes to find out how many log entries there are. Afterwards, we start a regular new segment. Let’s walk through an example. The producer just wrote log entries 7 and 8 before a network partition occurs isolating the current producer.

Due to the network partition, no more log entries can be written and health checks of the node will fail. This is why the control plane decides to spawn a new producer. This producer will then ask the coordinator to take over the log.

Now the coordinator will contact the log nodes of the latest segment and ask for the number of committed entries. Also, this will already seal the current segment so that no future writes of the current producer will make it through. After the coordinator receives the first answer, it will close the segment (knowing how many entries will be committed) and forward this information to the log nodes. As soon as the first log node responds, it contacts the new producer to inform that it can now write new log entries. This approach ensures atomicity: the moment the coordinator seals the current segment, the old producer is immediately cut off from writing, while the new producer can begin as soon as the handoff is complete.

Even if the old producer comes back online, it cannot write to the log anymore because the current segment is closed and the new segment is owned by another producer.

Test and Specification

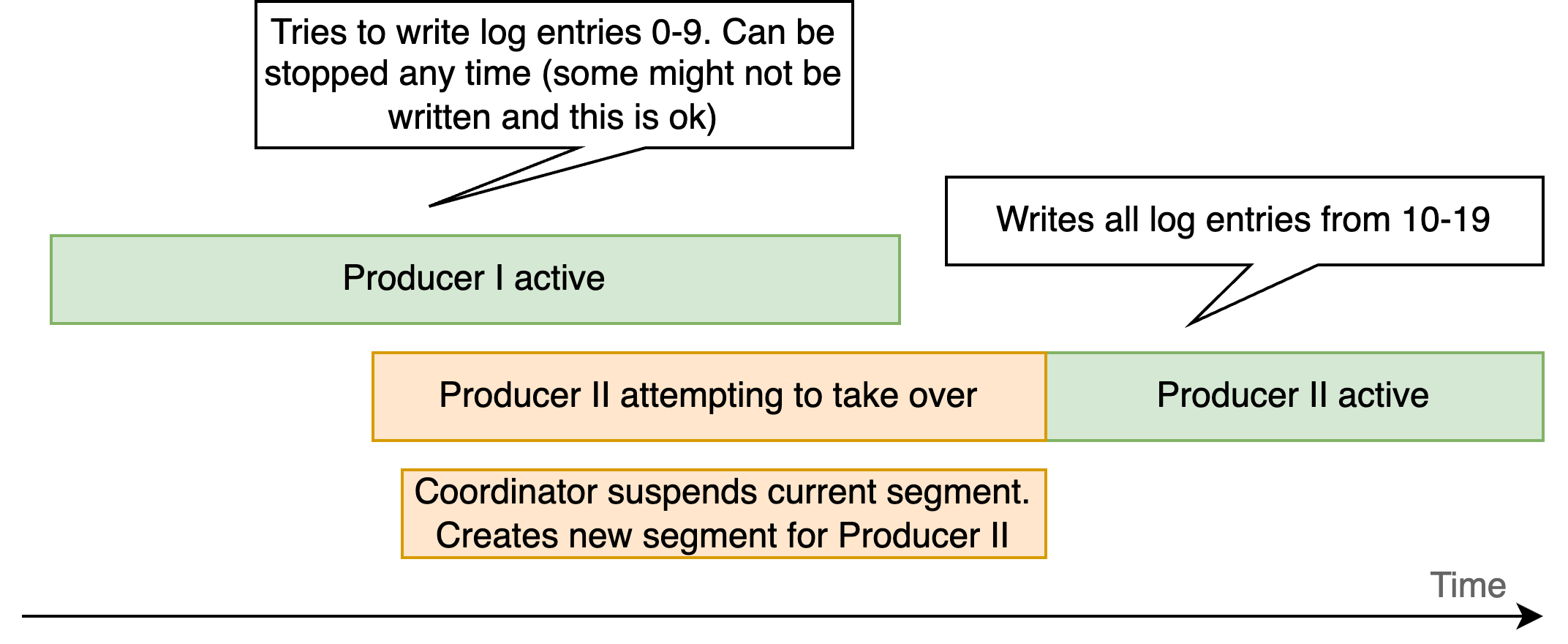

Another important question is how we test this. Our test creates the most challenging scenario possible: we keep the old producer running while a new producer takes over, then verify they never operate simultaneously.

The old producer tries to write log entries 0-9. At some point, the new producer becomes active, takes over and writes all log entries 10-19. We thus have to adapt all specifications to make sure they only check that all log entries 10-19 are written (because the old producer might not finish and this is intended). But how do we check with specs that no two producers are active at the same time?

A naive implementation (my first attempt) just checked: (i) who the current producer is (observing eProducerTakeOver) and (ii) if all committed log entries (observing eLogEntryCommitted) come from the current producer.

However, there is an edge case here where the old producer was still active, sent the last log entry to the log nodes and did not yet receive the acknowledgement. Then the new producer takes over and now the old producer receives the (delayed) acknowledgements and declares a log entry as committed even though it is not the current active producer. This is still correct linearizable behavior (if the acknowledgements were sent earlier, we would not observe this).

To fix this, we need to check what the highest log entry a producer tried to commit was when it was still the active producer. This is the only exception where it is fine if the old producer declares a commit as successful.

The full specification is as follows:

/*

Safety: makes sure there is only a single producer able to write log entries.

*/

spec SingleActiveProducer observes eLogEntryCommitted, eLogEntrySent, eProducerTakeOver, eMonitor_SingleProducer

{

var currentProducers: map[tLogId, Producer];

var highestPossibleCommit: map[tProducerLogPair, tLogSeqNum];

start state Init {

on eMonitor_SingleProducer goto WaitForEvents;

}

state WaitForEvents {

on eProducerTakeOver do (resp: tProducerTakeOver) {

currentProducers[resp.logId] = resp.producer;

}

on eLogEntryCommitted do (resp: tLogEntryCommitted) {

var prodLogPair: tProducerLogPair;

prodLogPair = (logId = resp.logId, producer = resp.producer);

// Currently the producer. All ok

if (resp.logId in currentProducers && currentProducers[resp.logId] == resp.producer)

return;

// Could be that this is a commit from a previous try when the producer was still active

assert prodLogPair in highestPossibleCommit,

format("Producer log pair {0} was not observed as producer", prodLogPair);

assert highestPossibleCommit[prodLogPair] >= resp.seqNum,

format("Seq number {0} by producer {1} is committed even though it is not currently the producer and was not tried while it was", resp.seqNum, resp.producer);

}

on eLogEntrySent do (resp: tLogEntrySent) {

var prodLogPair: tProducerLogPair;

prodLogPair = (logId = resp.logId, producer = resp.producer);

// we can only consider this as the highestPossibleCommit if it

// is currently the active producer

if (currentProducers[resp.logId] != resp.producer)

return;

highestPossibleCommit[prodLogPair] = resp.seqNum;

}

}

}

Run and Success

I ran the full specification for 3000 seeds with the following command on fish

for seed in (seq 0 3000)

echo "Running with seed: $seed"

if not p check --fail-on-maxsteps --max-steps 100000 --seed $seed

echo "Command failed with seed: $seed"

break

end

end

and did not find any errors. Running 3000 different scenarios with varying timing and failure patterns gives us high confidence in the correctness of our design.

Summary: From Simple Idea to Verified System

Over the course of this series, we’ve started from the elegant Taurus approach (just write to three nodes as long as possible) and specified a full distributed log system covering all failure modes. The journey revealed how even simple distributed system designs hide surprising complexity. We found many bugs using P that would have been hard to find and reproduce with integration tests or in production.

In this final post, we made it easier to use our log system from an operational perspective - we can just rely on a normal control plane to replace broken services and still do not have to fear split-brain scenarios.

Where to go from here

Our log system design is now thoroughly tested. Based on the elegant Taurus idea of writing to just three nodes, we developed our own design and probably a lot of design decisions differ - I am not aware of the full design of the log system used. In general, there are not many details out there about real-world log designs. If you have worked on one of those or have comments on the design developed here, I would be happy to chat and learn. Also, we have “just” developed a log system design - not a full-fledged implementation. Maybe someday this system can become a reality.

More broadly it’s exciting to see that formal verification is increasingly being used by cloud providers and academia to make sure their services are correct. While formal methods can’t catch every bug, they excel at finding the subtle race conditions and edge cases that are nearly impossible to reproduce reliably with conventional testing. This along with techniques like deterministic simulation testing, fuzzing and classical integration tests helps to make systems more reliable.

In this series, we specifically used P as formal verification tool and I found it very intuitive to use at some point. I really agree with the creators who claim that P is not just great for finding bugs but also as a thinking tool. Also, the VS code extension makes it really pleasant to work with it (including the graphical tools for log inspection described in the third blog post). If you are generally interested in formal verification, I would still recommend to play around with TLA+ as an alternative. It’s more mathematical and probably feels less intuitive but there is a lot of great material, e.g., Learn TLA+ or the blog by Jack Vanlightly.

Series

This post is part of a series. The full code can be found on github.

- P Verified Log 1: The Need for Verifification

- P Verified Log 2: Modeling the Happy Path

- P Verified Log 3: Introducing Failures

- P Verified Log 4: Debugging with PeasyViz

- P Verified Log 5: Single Producer and Outlook

This is the final post of this series (for now.) I would be really happy about feedback about the design, the writing of this blog post or general comments and discussions. Feel free to reach out on Linkedin.