P Verified Log 2: Modeling The Happy Path

In our previous post, we explored why the Taurus approach to distributed logs is compelling. Now it’s time to prove it actually works—starting with the simplest possible scenario where everything works perfectly. You can find the code of the full specification on github.

P Language Fundamentals

Before diving into code, let’s understand what the P language gives us. Think of P as a way to describe our distributed system as a collection of independent state machines that talk to each other through messages. Each machine—whether it’s a producer writing data, a log node storing it, or a consumer reading it—operates independently and communicates only through well-defined events.

What makes P powerful is that it doesn’t just run our system once. It systematically explores different timing scenarios and different execution interleavings. It’s like having a testing framework that tries millions of subtle variations we would never think to test manually.

When P finds a bug, it gives us the exact sequence of events that triggers it. When it doesn’t find bugs after exhaustive exploration, we can have real confidence in our design. For more information on the project, check out the P tutorials.

Our Simplified Log Architecture

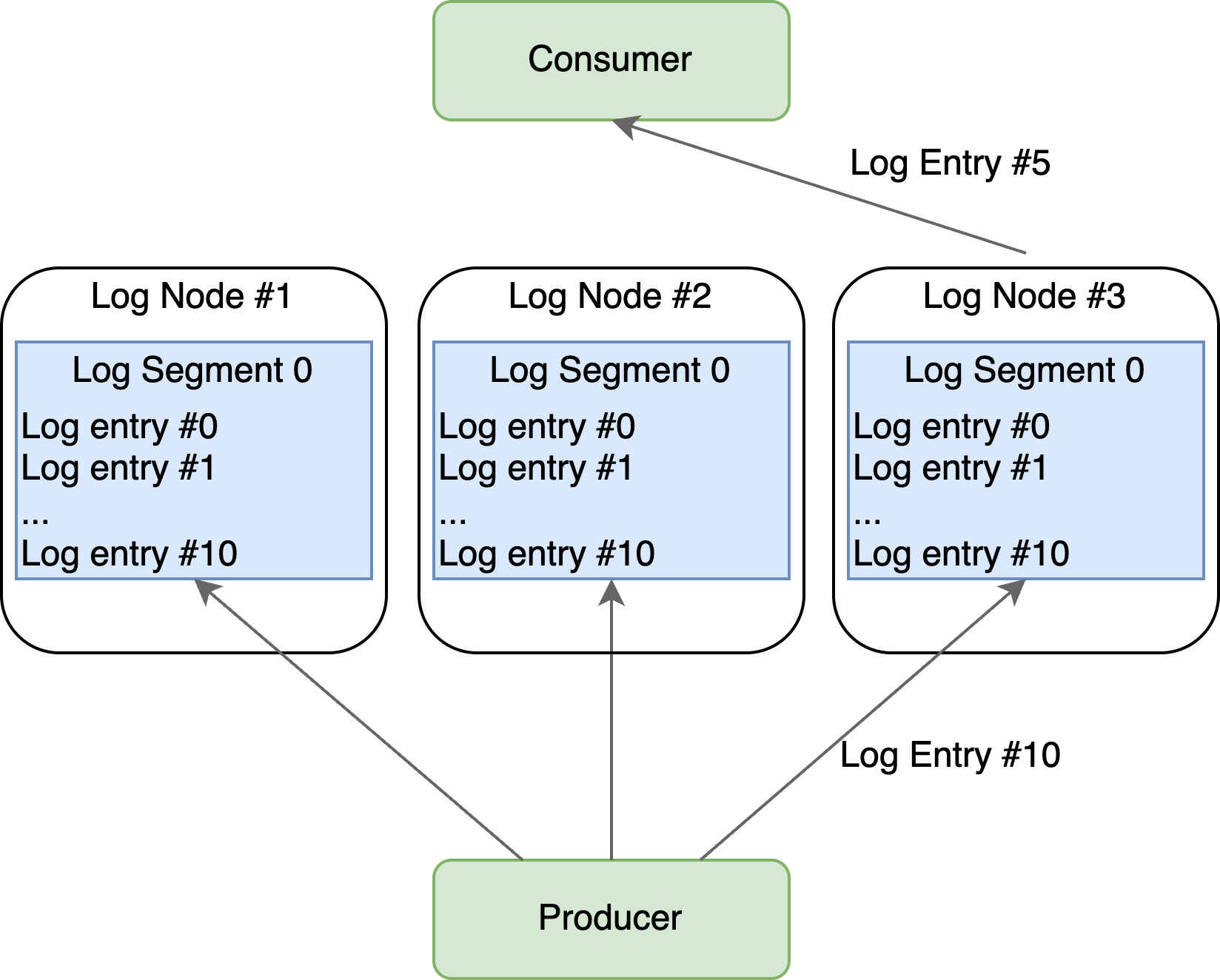

Let’s see how these concepts apply to our log system. Since we’re assuming perfect conditions, we can strip our design down to its essence. No node failures means no need for segments or complex coordination. Our system becomes beautifully simple: producers generate log entries and replicate them across multiple log nodes. Log nodes store entries in order and serve reads. Consumers read the entries sequentially.

The Write Path: Harder Than It Looks

Let’s walk through what happens when a producer wants to store a log entry. The logic seems straightforward—send the entry to all replicas and wait for acknowledgments:

state Produce {

entry {

var i: int;

while (i < sizeof(logNodes)) {

send logNodes[i], eAppendRequest, (client = this, seqNum = currentEntry, val = currentEntry);

i = i + 1;

}

}

on eAppendResponse do (response: tAppendResponse) {

if (response.status == APPEND_OK) {

appendAcks += (response.logNodeId);

if (sizeof(appendAcks) < sizeof(logNodes)) {

return;

}

// All replicas acknowledged, move to next entry

currentEntry = currentEntry + 1;

}

}

}

This captures the core idea: replicate first, advance only after all replicas confirm. But as we’ll see, even this simple protocol hides subtle correctness issues.

Log Nodes: The Deceptively Simple Part

Each log node’s job appears trivial—store incoming entries and serve reads:

on eAppendRequest do (req : tAppendRequest) {

announce eLogEntryStored, (seqNum = req.seqNum, logNodeId = logNodeId);

log += (sizeof(log), (seqNum = req.seqNum, val = req.val));

send req.client, eAppendResponse, (status = APPEND_OK, seqNum = req.seqNum, logNodeId = logNodeId);

}

For reads, we simply return what we have:

on eReadRequest do (readReq : tReadRequest) {

if (sizeof(log) <= readReq.offset) {

send readReq.client, eReadResponse, (status = READ_NO_MORE_ENTRIES, seqNum = 0, val = 0);

return;

}

send readReq.client, eReadResponse, (status = READ_OK, seqNum = log[readReq.offset].seqNum, val = log[readReq.offset].val);

}

This looks obviously correct. Store entries as they arrive, return them to readers on request. What could go wrong?

Consumers: Persistent Optimism

Consumers follow a simple pattern—keep trying to read the next entry:

state Consume {

entry {

send logNode, eReadRequest, (client = this, offset = currentOffset);

}

on eReadResponse do (response: tReadResponse) {

if (response.status == READ_OK) {

currentOffset = currentOffset + 1;

currNumLogEntries = currNumLogEntries + 1;

}

goto Consume; // Retry regardless of result

}

}

The persistent retry ensures consumers eventually see all data, even if some read attempts hit empty spots while producers are still writing.

Formal Specifications: The Heart of Verification

Here’s where formal verification reveals its power. We don’t just run the system and hope it works—we define precisely what “correct” means and let P verify those properties hold under all possible executions.

Our first property is durability—consumers should never see data that hasn’t been properly replicated:

spec Durability observes eLogEntryStored, eReadResponse, eMonitor_Durability {

on eLogEntryStored do (resp: tLogEntryStored) {

logStoreEvents[resp.seqNum] = logStoreEvents[resp.seqNum] + 1;

}

on eReadResponse do (resp: tReadResponse) {

assert resp.seqNum in logStoreEvents;

// requiredReplicas is the number of copies requested

assert logStoreEvents[resp.seqNum] >= requiredReplicas;

}

}

This specification acts as a watchdog, tracking how many replicas have stored each entry and asserting that consumers never receive under-replicated data.

Our second property is progress—all entries should eventually reach consumers:

spec Progress observes eMonitor_Progress, eReadResponse {

hot state WaitForReplies {

on eReadResponse do (resp: tReadResponse) {

reportedLogEntries += (resp.seqNum);

if (sizeof(reportedLogEntries) == numLogEntries - 1) {

goto AllLogEntriesConsumed;

}

}

}

}

The hot state annotation tells P this state must eventually be exited—if the system gets stuck here, we have a liveness violation.

Our First Reality Check

Let’s run P and see what happens:

p compile && p check --fail-on-maxsteps --max-steps 100000 --seed 3

Instead of the satisfying green checkmark we hoped for, P immediately throws an error:

Assertion Failed: PSpec/Specs.p:41:7 Sent log event to client that is not replicated to 3 replicas

This is actually excellent news. P found a subtle bug that we completely missed—and this is in our “simple” happy path scenario with no failures at all.

The Race Condition We Didn’t See

The bug reveals a classic distributed systems gotcha. Here’s what happens:

- Producer sends entry X to all three log nodes

- Log node A receives and stores entry X first

- Consumer asks log node A for new data

- Log node A happily returns entry X—even though nodes B and C haven’t stored it yet

- Our durability specification catches this violation

This is a race between replication and reads. Even though the producer waits for all acknowledgments before proceeding to the next entry, consumers can still read under-replicated data from fast replicas.

The Fix: Controlled Staleness

The solution requires us to be more careful about when we expose data to consumers. We can’t just return the latest entry because we can’t be sure it’s fully replicated yet. Here’s our fix:

on eReadRequest do (readReq : tReadRequest) {

// Only return entries up to the second-to-last one

if (sizeof(log) - 1 <= readReq.offset) {

send readReq.client, eReadResponse, (status = READ_NO_MORE_ENTRIES, seqNum = 0, val = 0);

return;

}

send readReq.client, eReadResponse, (status = READ_OK, seqNum = log[readReq.offset].seqNum, val = log[readReq.offset].val);

}

This implements controlled staleness. Instead of returning the most recent entry, we only return entries up to the second-to-last one. The reasoning is subtle but sound:

When we see entry N+1 in our local log, we know the producer has moved on from entry N. Since the producer only advances after receiving all acknowledgments, entry N must be replicated everywhere. We can safely expose it to consumers.

This approach avoids coordination overhead while maintaining our safety guarantees.

Verification Success

With this fix in place, let’s run P again on the problematic seed:

p compile && p check --fail-on-maxsteps --max-steps 100000 --seed 3

We can even run P with a timeout to explore more schedules:

p compile && p check --fail-on-maxsteps --max-steps 100000 --seed 3 --timeout 800 --explore

P systematically explores different execution orders and timing scenarios without finding violations. We have confidence that our design satisfies both safety and liveness properties—at least in our simplified world.

The Road Ahead

Our current model assumes an ideal world: no crashes and a reliable network. In the next post we will look at what it takes to survive such failures.

Series

This post is part of a series. The full code can be found on github.